Starting a new professional role is rarely experienced without some degree of trepidation. For most people the learning curve is steep, with multiple expectations to make a positive impact, ‘keep up’ and learn fast—and that’s often just to get through probation. Yet these same challenges can be wrongly interpreted as threats, because they trigger the brain function which scans for sources of potential danger. Neuroscience studies reveal that being uncertain about the potentiality of a threat, as well as how serious it might be should it materialise, can lead to a significantly greater level of stress response than if we are made fully aware of a threat in real life.

A new working environment, people and processes, and even the job itself provide exactly this kind of uncertainty – and impact – on the individual. In these scenarios, it’s hardly surprising that many new recruits doubt themselves or even ask “am I cut out for this?” So how do we navigate the uncharted waters of a new professional environment and develop the mindset to thrive in our first few months?

Lean in, monitor your resistance

On entering the workplace, our response to challenges depends largely on what has happened to us before; our upbringing, education, the experiences we’ve accumulated – in work and life – and of course, the relationships we’ve had. To perform at one’s best under pressure, it’s important to have a level of mental resilience, and this is where effective coaching and training can help develop our mental muscle to respond with what performance scientists refer to as ‘growth mindset’.

Stress is a part of life. A certain amount is inevitable and even good for us. Provided that we can cope, stress will stimulate our learning and development. It is when we can’t cope it becomes negative. When the demands of the situation overwhelm our current level of coping skills and resources (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

Metaphorically, this is not dissimilar to our body’s physical potential. If you move or stretch too far (or in the wrong way) during exercise, you get injured. Conversely, if you don’t exert yourself enough, your body will stay within its current limits. Your muscles may even reduce in size or flexibility depending on the demands made of them. However, with effective coaching and training our strength and flexibility can be increased safely.

Of course, we are all different; one person’s debilitating stress is another’s motivation. ‘The evolutionary function of our human stress-response only poses an issue when the perceived threat becomes intolerable, and exerts a high allostatic load’ (McEwen and Stellar, 1993).

What’s your story about stress?

Not only do our life experiences and conditioning determine our resilience, our internal narratives around handling and overcoming challenges also play an important part in influencing how we individually relate to stress.

Just like our relationships, this isn’t fixed. We can understand, then improve, our level of stress resilience and even leverage it for a fast and helpful burst of motivation. If we know when we’re responding negatively to a threat, we may be able to use our awareness to reframe that stress – and our relationship with it – into a more empowering narrative.

Practicing the Art of Mind (set) Over Matter

Executive coaching often starts by engaging the client to develop the most effective mind-set. In fact, when it comes to stress, research shows that mindset not only affects your performance but also has the ability to deeply and directly impact your physiological state and ultimately, health. In Kelly McGonigal’s eye-opening book The Upside of Stress, she argues, “Even if you are firmly convinced that stress is harmful, you can still cultivate a mindset that helps you thrive.”

The key word here is cultivate – a verb that implies nurturing (which is, of course, a considered action). However, before we can put ourselves on this track, we must first understand how our inner storytelling so often short-circuits this kind of mindset. A key definition we use about storytelling here; a story about an event is an episode, whilst a picture of the broader trajectory of our professional or personal life becomes a kind of running narrative. Put differently, our habitual stories are those that we’ve come to cling to over time. Meanwhile, our personal narratives describe more than a moment; they describe our lives.

If we subscribe to any given narrative deeply enough, we know from neuroscience that this can impact on how we behave and certainly whether we might ‘rise to a challenge’, or retreat when things get tough. It’s akin to a kind of stress-based ‘sliding doors’ moment, whereby how we choose to respond to stress can impact the broader narrative entirely. This is no truer than in a professional setting when a new recruit wants to make a positive first impression. However, it’s important to remain authentic. “Consciously adopt a persona you can live with”, as Nick Walkley, CEO of Homes England, describes when we asked him what advice he’d give a new recruit at senior level. He adds, “The ‘first 100 days’ is now a ‘thing’ so you have to decide how you’re going to be, because people will watch. Be humble, as everything you ‘think’ is probably wrong!”

Rewriting the Narrative

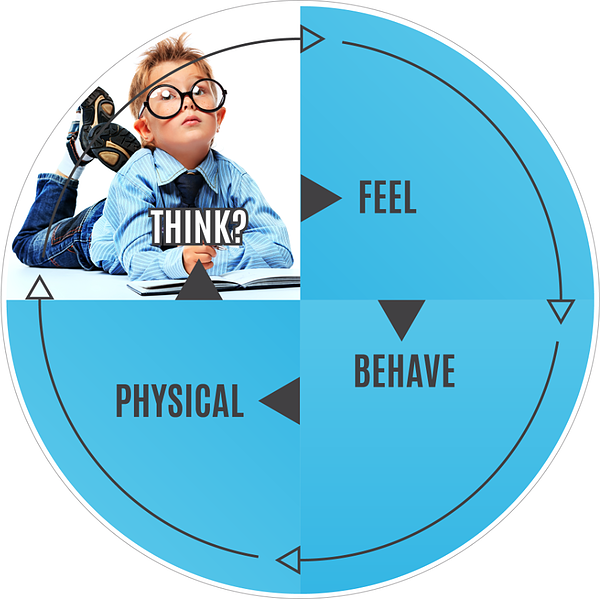

The stress-narratives we create (and buy into) are therefore powerful influences on our wellbeing and performance. Cognitive Behavioural Therapist Christine Padesky uses a beautifully simple model to explore the narratives that impact our wellbeing. Her model relates the power of our thoughts to influence our emotions and how these, in turn, drive our behaviour. Biochemical messages from the body are also transmitted back to the brain (which can be positive or negative). And so the cycle goes on.

Clearly, the language we use to describe a situation and the people around us and ourselves, will have an effect on our feelings, subsequent behaviour and ultimately, our physical body.

Additionally, when it comes to naming the issue, we can begin to be clearer about what is happening, and differentiate between our view of reality and the interpretation or ‘story’ we conjure up in order to make sense of situations. This is not to diminish the power nor value of the interpretation we put on a situation, but rather, to recognise the influence it has over us. Most importantly, this practice enables a healthy amount of detachment from our mental narrative and what’s actually going on.

We’ve coached a number of people who have named one of their biggest fears as having ‘imposter syndrome’. They feel as if they ‘don’t belong’ or they ‘haven’t earned their position’, they are acting it out, or ‘they aren’t worthy’. This fear is surprisingly common for many people and, to some extent, we’ve all felt like an imposter at one point. Very successful people have told us they just hope they’ll ‘never be found out’.

It is therefore helpful for an individual to be as clear possible about their role-narrative. So here’s a thought for you: you can’t be an imposter in your own script. In other words, if you’ve written the role you have defined and play, you own it. You can’t be an imposter.

Developing ‘the Observer’

One helpful technique we’ve used in the corporate space involves developing what is referred to as the ‘associated and dissociated’ viewpoints. This involves the practice of checking in as a neutral observer of your ‘self’ and your objectives. It could be as simple as asking, “what is it that I want to achieve in this scenario and what will it look like when I achieve it?”, as opposed to assuming “no, it’s not working, it’s a disaster!” It sounds obvious, but the art of detaching, then reframing, is one of the fastest routes to progress for clients prone to ‘disaster’ language and reactive, knee-jerk negativity. As Matthew Costello, Senior Partner Development Manager at Microsoft, puts it, “Never forget the thing that grounds you outside of work – the thing you hold onto in order to step outside the circle, and away from the situation”. So as much as we believe that mindset is mastered by changing the narrative, it’s just as important to first take a deep breath, then step back and disengage altogether.