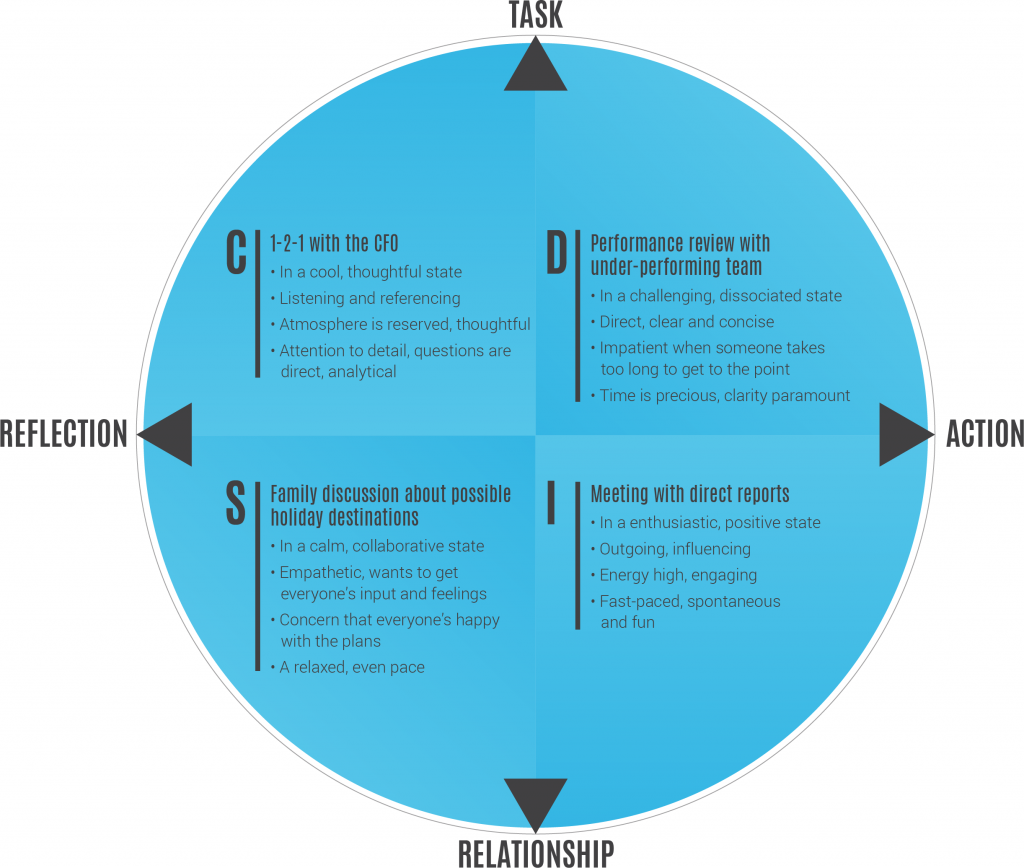

Trying to assess and predict behavioural traits dates as far back as Ancient Greece. In executive coaching and the corporate sector, one of the most widely used tools that claims to help define these traits is DISC – a model that divides behavioural patterns into four quadrants: dominance (D), influence (I), steadiness (S) and conscientious (C). These four behavioural patterns are often mapped like a compass – North being the direction of task-orientation, South is the direction of the warmer, sympathetic, people-orientated behaviours, East is the direction of action and West, the direction of reflection.

The principle behind DISC is that people’s behaviour sits along a continuum between task and relationship orientation, and then on the other continuum between action and reflection orientation. However, in our experience, DISC’s value is often greatly misunderstood and used by many as a fixed-point, unchangeable reference for an individual’s behaviour. By contrast, behavioural patterns are known to switch in relation to the context and emotional state we inhabit in a particular moment. Undoubtedly, a fixed perspective leads to labelling, and labelling undermines any effort to develop the behavioural flexibility required to communicate and influence well.

Outstanding communicators and leaders move between all four DISC behavioural references as appropriate, guided by what they observe in others, their self-reflections, and what they think will have the greatest impact in the moment.

We can all access the four patterns, and probably already do in certain contexts. Sometimes we even do so within the course of a single day. A client of ours, Sarah, provides a great example of this:

Judging books by their covers

Humans are quick to make decisions about someone else’s behaviour. We can rapidly assign a rich (and possibly inaccurate) narrative to someone within minutes of meeting them. In other words, we are fond of labelling and making decisions about people quickly. It’s a simple, tribal and often unconscious way to identify if they’re ‘one of us’ or not.

Have you ever judged someone as being like ‘this’ or ‘that’ and written them off as a potential friend, only to find out by chance that they are completely different to your initial expectations? We’ve all been there, and we surely thought our first impression was spot on. Until it’s proven otherwise.

There’s an evolutionary reason for this; quick decisions were a means of staying alive and reducing the risk of danger. It stands to reason therefore, that we need to be mindful of this trait when using DISC. Our tendency to label can cause us to use DISC to make assumptions that people’s behaviour in a certain context is an expression of their personality. Worse still, once labelled (or self-labelled), the person can find themselves enacting the characteristics of that label and behaving to ‘type’ – perhaps to their own detriment.

Changing the behavioural script

The good news is that behavioural patterns can be changed relatively easily with some focused effort. As we know from continuous advances in neuroscience, neuroplasticity enables all of us to ‘rewire’ old programming. Also, we have the ability to reframe (sometimes immediately) our observations and experiences of others and their impact on us. We have used the DISC tool to help countless executives enhance their communication and performance in this way. Bev, a senior executive client, is a fine example of this.

Despite being the most experienced and knowledgeable member of the team, Bev felt undervalued. She thought her boss didn’t listen, withheld information, and she admitted that she had “lost faith” in the leadership. As someone who liked to collaborate and be included, being excluded from information and a lack of transparency created a strong sense of conflict in Bev. This, in turn, led to inner narratives along the lines of “they don’t trust me, ask my advice or listen when I do”. Unsurprisingly, her sense of risk and anxiety rose.

Working with Bev, we explored the habitual patterns of behaviour that her boss, and boss’s boss, were exhibiting in order to help her see the situation from a different perspective. Using the DISC model, Bev noticed their task-driven behaviour, the potential stress they were under and how this was impacting on them. They both displayed strong tendencies to behave in D mode – demanding task completion, and holding back information that they deemed to be irrelevant to her ability to deliver.

We then played with some positive assumptions; she was encouraged to assume their intentions were good, productivity-centric and that they were ultimately grateful for her help. Bev visibly relaxed. She’d taken a moment (and a step back) to consider ‘behaviour’ as separate from ‘identity’. She’d also created some distance between her self-sabotaging narrative, versus the very possible constraints, stresses and narratives her bosses were experiencing themselves.

When we use DISC in this way, clients get the wide angle lens perspective on a situation, which facilitates a conscious shift in behaviour that yields better rapport and influence all round.

Raise awareness, increase flexibility

DISC’s strength lies in its simplicity. Used well, it can quickly help to bring awareness to behavioural patterns in the moment; both our own and others. It helps us consider what our likely conditioned response patterns tend to be and why these patterns might trigger conflict with another’s. Taken to the extreme, this can sometimes feel like we are speaking a different language to the person we’re communicating with. And in some ways, we are. The important element to remember here is it’s perfectly possible to speak multiple ‘behavioural’ languages—you just need to have the insight into your own and the other person’s patterns to know which ‘language’ to use in that moment. When clients aren’t able to grasp this, relationships are inevitably compromised.

“Used well, DISC is an opportunity to actually break away from labels – it becomes liberating not limiting.”

James Stringer, Co-CEO, Brave

If we can broaden our interpretation of how to use DISC well, it’s possible to grow in self-awareness, better able to identify what makes a person happy or uncomfortable at work, and how to cooperate with others to strengthen professional relationships. Combined, each element has the very real ability to positively impact sales performance and leadership and is a welcome reminder that what we do is not who we are.